Blog Alloy Numbering Systems

By: Dave Olsen

Surfing around the reaches of cable TV the other night, we came across an airing of Atlas Shrugged. In the book/movie, Hank Rearden has developed a brand new light-weight high-performance alloy for railroads that threatens to revolutionize the industry. Called “Rearden Metal” (once his career-savvy Marketing guys get a hold of it), Hank is protective of the chemistry and properties of the metal – other than to assert its superiority in the manufacture of train rails.

The burgeoning US rail industry in the late 1800’s was facing Rearden-like conditions. Steel used in rail manufacture was of inconsistent quality – suppliers differed, manufacturing lots differed, and expectations between buyer and seller differed. A take-it-or-leave it attitude prevailed.

Enter Charles Dudley, the father of ASTM, now the American Society for Testing and Materials. Dudley engendered a collaborative process as a means to develop and adopt standards that were acceptable to both producers and users. What began with railroad steel has expanded through the efforts of ASTM, DIN, BSI, JSA, AFNOR and others to thousands of other materials used in countless applications.

ASTM standards describe the composition of alloys, minimum mechanical properties than the materials must exhibit when test bars are evaluated, and standards for how those tests are to be done. Customers know what to expect when designing components and suppliers know what properties must be achieved.

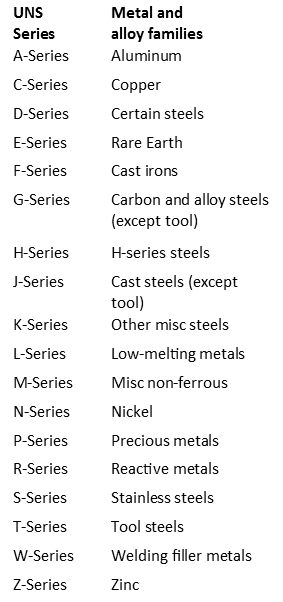

To sort through the range of alloys that were available and organize them into families, the ASTM in conjunction with the SAE devised a Unified Numbering System, or UNS. The UNS has become a shorthand descriptor that allows users and suppliers to understand material callouts across industries and applications – while preserving the expectation of material performance.

Other common designations like those developed by the Alloy Casting Institute classify materials based on their application and chemistry. For example, the ACI designation for a stainless alloy may start with a “C” if it is used for Corrosion-resistance, or “H” for a Heat-resistant environment. The other positions in the convention indicate amounts of included elements.

If we consider the common stainless material CF8M:

- The “C” in CF8M indicates that it is a material typically used for corrosion resistance. To be considered stainless, a minimum amount of Cr must be included – about 12%.

- The second position is a letter that indicates how much chromium-nickel the grade contains. An “A” indicates the least amount of Ni and “Z” is the greatest amount. So a CF8M material will have relatively more Ni than a CA15, indicated by comparing the “F” to the “A” in the ACI designation.

- The next position, a numeral, indicates the maximum amount of allowable carbon. The “8” in CF8M indicates that there is no more than 0.08% carbon; CA15 is allowed no more than 0.15%.

- The final position(s) indicates other alloying elements. The “M” at the end of CF8M indicates that Molybdenum is included.

It’s been a long time since the early railroad days to get to where standards are accepted and components of materials expectations understood.

As an aside, if you watch the Atlas Shrugged movie, you will notice that no one is wearing appropriate safety equipment or following even rudimentary safety procedures while out in the shop watching “Rearden Metal” being poured. But that is a topic for another day and one that will include other appropriate ASTM standards.